The Stew BLOG

An ROI Worth More Consideration: Population Health as a Path to Economic Development

More and more, we are understanding the connection between health and the overall well-being of people and their communities. One expression of this is Health in All Policies, where the goal is to ensure that all decision makers are informed about the health consequences of various policy options during the policy development process.

I’d like to take this concept another step—or leap—forward. It’s important but it’s not enough to understand the impacts on health when we’re making decisions about jobs, transit, crime, social services, housing, etc. It’s time to also consider the impacts from health in these sectors. In other words, investments in evidence-based health interventions can be expected to yield enormous community and economic benefits, and we ought to be paying more attention to that.

For example, suppose you want to improve lifetime earnings. A typical response would be to invest directly in education or job training (and those are good things). But, what about investing in infrastructure that reduces lead poisoning? Children with high lead levels in their blood are more likely to require special education, have lower IQs and ADHD, and be involved in crime. They are less likely to be ready to start school and to graduate from high school.

A 2009 Environmental Health Perspectives Journal article investigated the costs and benefits of lead hazard control for children under the age of six and found that, for every dollar spent on lead hazard control, $11-$227[1] were returned in benefits. The vast majority of these benefits accrued in the form of higher lifetime earnings and associated tax revenues, but the financial benefits also reduced costs in a variety of sectors, including special education, health care, and criminal justice. Now that’s community and economic development!

Once we start to treat health as a linchpin to community and economic development, we can begin to insist on different investment decisions and improve our programmatic approaches to power boost results. What could we be asserting to make this point of view more commonly understood? Here are three ideas:

1. Health is an economic engine.

There has long been evidence that wealth leads to health. But does health lead to wealth? It seems so.[2] A series of 2008 symposium papers, entitled Health And Economic Development: Reframing The Pathway, argued for viewing “health as an economic engine” in which “improving economic conditions to improve health, and improving health to improve economic conditions, leads to the possibility of ‘virtuous cycles’.” They went on to conclude that as the cycles continue, there are ever-improving health and economic conditions. Interestingly, some of the authors, David Mirvis and Joy Clay, further posited that “a health intervention…maybe a necessary precursor or parallel to economic interventions. The success of an economic intervention may be dependent upon the health of the population, as an unhealthy workforce may be unable to support the needs of an economic industrial stimulus.”

This case for health as an economic engine seems fairly obvious when it comes to personal wealth and business profits, as demonstrated in these stats:

- One additional chronic disease at age 16 is associated with a 5% reduction in the probability of employment at age 42.

- Raising the average birth weight of low birth weight babies to the mean birth weight of all U.S. babies increases their lifetime earnings an estimated 26%.

- The overall economic impact of absenteeism and presenteeism (working while sick) from common chronic diseases exceeded $1 trillion in 2003, and may reach $5.7 trillion by 2030.

Finally, it appears that health spurs economic growth through a variety of macroeconomic factors, such as increasing savings rates and foreign investment, improving social structures and community cohesion, and altering the long-term demographics of a population. One study that looked at 13 developed countries found that a 1% increase in life expectancy resulted in an average 6% increase in total GDP in the long run, and a 5% increase in GDP per capita. Another study concluded, “good health has a positive, sizable, and statistically significant effect on aggregate output.”

2. Population health investments can spur jobs, earnings, and fiscal soundness.

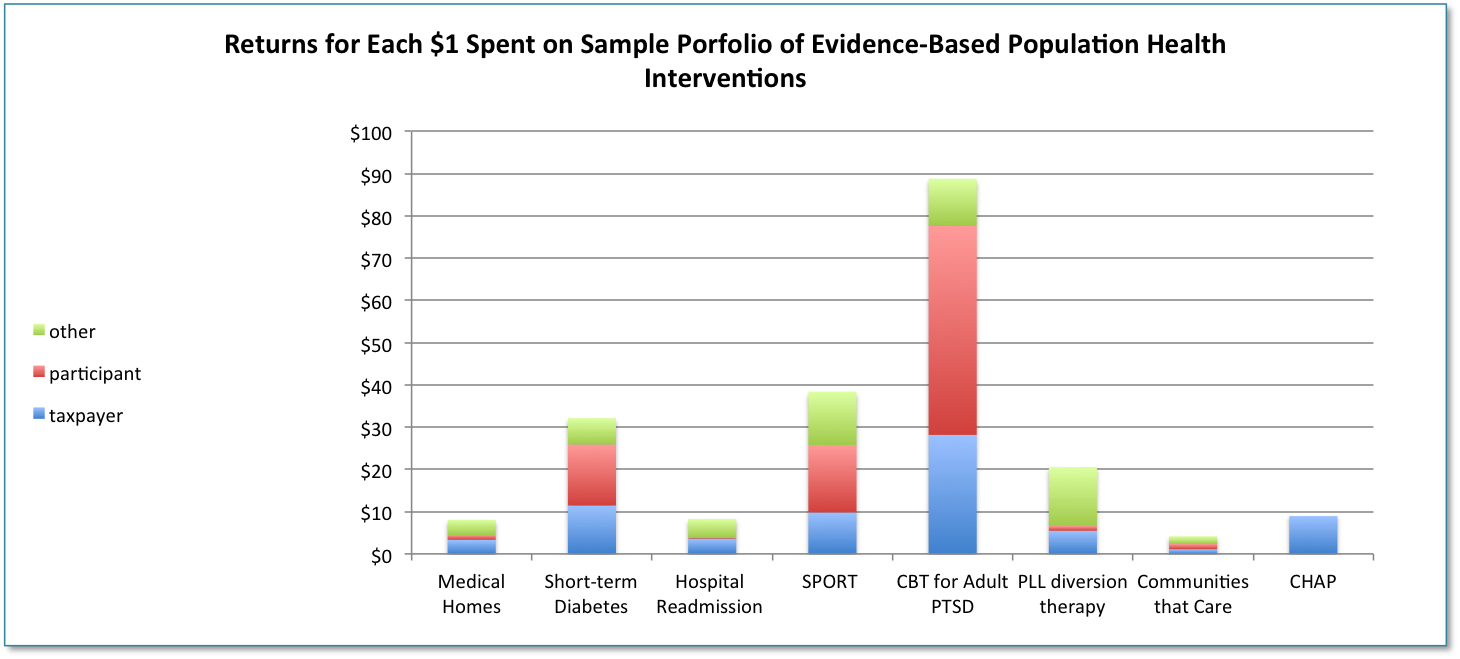

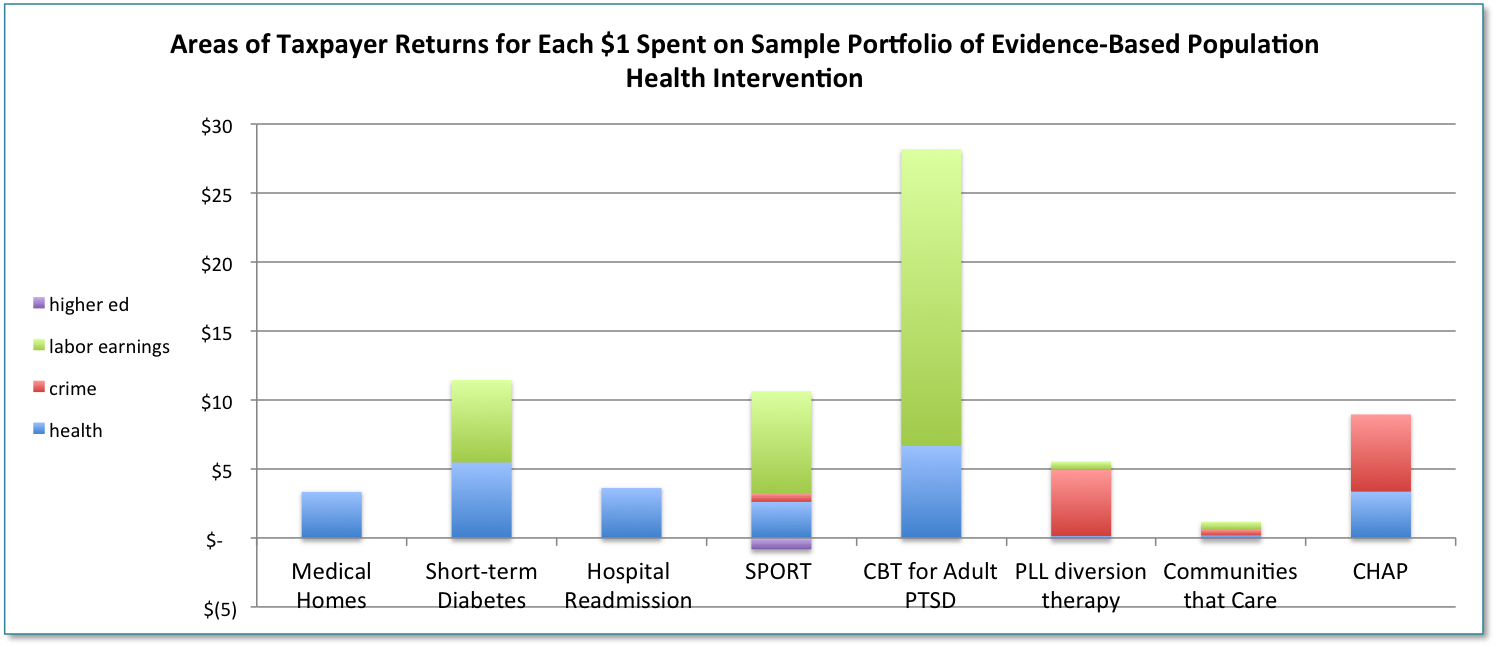

A few months ago, I was poking around one of my favorite websites, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy. From its cost-benefit data, I constructed a portfolio[3] of various interventions related to population health. I simply chose a mix of population health interventions, from clinical to school-based to community-based. The returns from this portfolio are shown in the two graphs below (see the footnote for detail on all those acronyms):

Notice on the first chart that benefits are strong for taxpayers (good for the fiscal health of communities) as well as the actual participants in the program. The second graph shows that many of the returns to taxpayers come in the form of higher taxes due to higher labor earnings. In short, these interventions have a strong positive impact on jobs and earnings.

Did I cherry pick the interventions? Of course I did! Why would one invest in the lowest return stocks in the stock market? But go to the website, and you’ll see that there are plenty of other high return investments.

3. Key investments we currently make in economic development are underperforming.

Business tax incentives aimed directly at job creation as well as business retention and expansion–often administered through enterprise/empowerment zone type programs–are a ubiquitous instrument of economic development. In a just released paper, the Upjohn Institute estimated that, nationally, state and local tax breaks for business incentives total $45 billion, yet “incentives do not have a large correlation with a state’s current or past unemployment or income levels, or with its future economic growth.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco wrote in its March 2015 Economic Letter: “Our overall view of the evidence is that state enterprise zone programs have generally not been effective at creating jobs. Moreover, even if there is job creation, it is hard to make the case that enterprise zones have furthered distributional goals of reducing poverty in the zones, and it is likely that they have generated benefits for real estate owners, who are not the intended beneficiaries.”

These general findings are echoed in study after study at the state level.

- An independent evaluation of New Jersey’s Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ) program found that, from 2002 to 2008, the state invested a total of $276.6 million but received only $0.08 in state and municipal tax revenues in return and $0.83 of “ripple” effects on the economy (i.e., net negative returns). And all 37 UEZ municipalities were in the bottom 10% of distressed cities according to New Jersey’s 2007 Municipal Revitalization Index.

- The California auditor found, “We could not determine whether the $1.5 billion of foregone revenue related to a research and development (R&D) credit in fiscal year 2012-13 is fulfilling its purpose or benefitting the state economy.”

- In a review of business incentives in New York state, evaluators wrote: “In the 2013 tax year, New York State provided an estimated $1.7 billion in 50 business tax credits to encourage taxpayers to engage in specific activities. . .There is, however, no conclusive evidence from research studies conducted since the mid-1950s to show that business tax incentives have an impact on net economic gains to the states above and beyond the level that would have been attained absent the incentives.”

Why would we spend our money this way? If our personal investment portfolios had such mixed results, I don’t think we’d hesitate to pick new stocks. It’s incumbent on us to be optimizing our public investments as well.

In fairness, many states– Maine and New Jersey, for example–are beginning to evaluate and call for reform of their business tax incentive programs. As best I can tell, however, there remains no wholesale rethinking of the general approach. We have to ask ourselves: are business tax credits for job creation the best way to increase jobs and therefore the income of residents in a community?

Maybe offering business tax credits for creating health (a la Mirvis and Clay) would be a higher yield approach. For example, suppose the portfolio mix I used to generate the graphs was the right mix for New York State, and further suppose that New York spent about half of its tax credits ($800 million) on this portfolio, and that the yield was only half what the evidence projects. In this scenario, taxpayers would see a yield of more than $3.6 billion, and participants would reap another $4.5 billion of benefits, mostly in the form of higher labor earnings.

No doubt this is an overly simplistic calculation—variables such as effect size and dosage, differences in costs/taxes between New York and Washington, and potential interactions across interventions would need to be taken into account for a proper analysis. But the point is that, even if we cut returns in half from what the evidence suggests, we still have some very healthy yields—very healthy compared to current investments. And that is an ROI worth some serious consideration.

Do you agree? Let me know your thoughts by commenting below or email me at [email protected] or find me on Twitter @stacymbecker

[1] Yes, it’s a big range, due to calculating a series of conservative estimates for costs as well as benefits in each area. But even the most conservative estimate is an impressive return!

[2] Quotes and information in this paragraph are from symposium papers published in the Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, Summer 2008: “Health And Economic Development: Reframing The Pathway,” Mirvis and Clay and “Health As An Economic Engine: Evidence For The Importance Of Health In Economic Development,” Mirvis, Chang, and Cosby.

[3] Data from Washington State Institute for Public Policy, except the CHAP program results which are reported from Maternal and Child Health Journal. Programs: Medical Homes–for high risk patients; Hospital Readmission Prevention– for the general population; SPORT–a healthy behaviors curriculum; CBT for Adult PTSD–Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adult Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; PLL diversion therapy–Parenting with Love and Limits diversion program for juveniles; Communities that Care–for at risk youth; CHAP–Community Health Access Project to prevent low birth weights