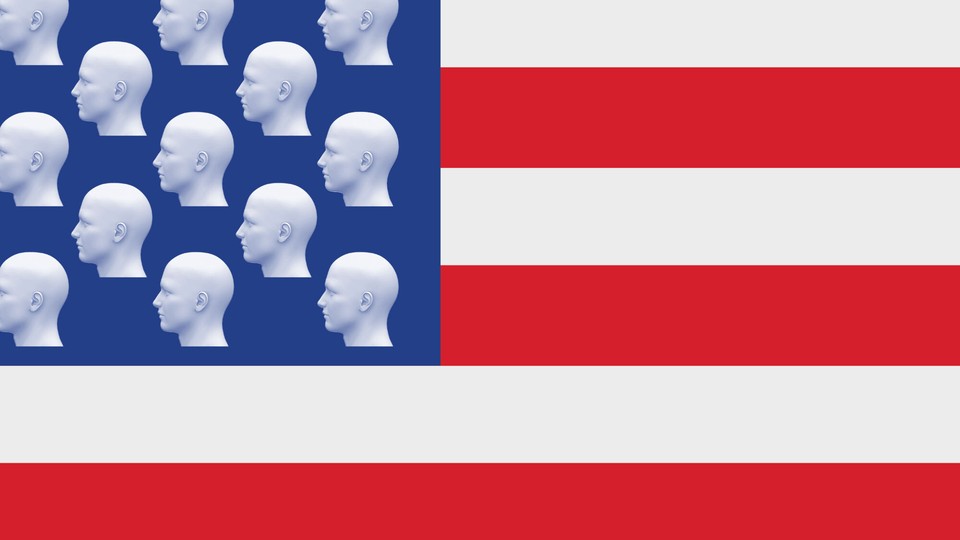

The Coming Mental-Health Crisis

Congress must rethink the American approach to mental-health care during the pandemic.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, America’s infrastructure for mental-health and addiction services was fragmented, overburdened, and underfunded. The coronavirus has put far more stress on that broken system. So far, Congress has failed to shore it up. That oversight will prove harmful to patients and their families and costly to insurers and taxpayers. Mental-health disorders were already at the top of the list of the most costly conditions in American health care even before COVID-19.

The organizations that provide behavioral-health services face their greatest economic challenge in memory. As an online survey of 880 such organizations recently found, the pandemic is forcing practices to reduce services, provide care to patients without sufficient protective equipment, lay off and furlough employees, and risk closure within months. For people with serious mental illness who are trying to get treatment or access their medications, the doors of many community mental-health centers are closed. For those with both mental illness and COVID-19, including a large number who are homeless, no care is available, and they are at risk of exposing others.

Congress must do much more to help mental-health providers adapt.

First, lawmakers should provide explicit financial support for mental-health and addiction clinicians to provide meaningful, timely, and convenient care. Any enhanced funding to Medicaid programs or hospitals should explicitly include an allocation for mental-health resources, including prioritization for programs that integrate mental-health resources in emergency rooms and other hospital wards.

Second, the pandemic is a prime opportunity to rethink the American approach to mental-health care in its entirety—to adopt a new vision and create an integrated system of services that reaches into settings as varied as primary care, our schools, our prisons, our workplaces, and our homes. Such a system will require substantial investment.

Yet better mental-health services have not been a priority during the current pandemic. The CARES Act, the $2 trillion relief bill that flew through Congress, included a paltry $425 million for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. That investment is welcome, but it also underscores the dearth of official interest in this vital area. For reference, $425 million is less than 1 percent of the total amount invested in the airline industry and an even smaller fraction of the $185 billion dedicated to health-care providers as a whole. Crises offer policy makers a chance to take a fresh look at the nation’s problems. But Congress is failing to capitalize on the mental-health crisis in any meaningful way.

Recent data from the Kaiser Family Foundation illustrate the need for both a short- and long-term strategy for better mental- and behavioral-health care.

When asked if worry or stress related to the coronavirus had hurt their mental health, four in 10 in the Kaiser survey reported that worry or stress had led to sleep problems. Others reported that the coronavirus had caused them to experience a variety of health-related ills, such as frequent headaches or stomachaches and increased alcohol or drug use. If these problems are not addressed now, they may fester and worsen in the future.

The challenge is daunting—and not just for those who already face mental-health and substance-abuse issues and those at risk because of the changes in their life caused by the pandemic. The people crucial to fighting the coronavirus are vulnerable as well. Most telling in this latest round of survey data is the impact that COVID-19 is having on essential workers, including health-care personnel. Two-thirds of those surveyed who live in a home with a health-care worker reported that the worry or stress from the virus had caused them to experience at least one adverse effect on their mental health or well-being sometime over the past two months. Recent suicides and increased calls to crisis lines dedicated to health professionals and other essential workers underscore the size of the unaddressed problem.

That problem will not solve itself. And the longer the crisis continues, the greater the danger to Americans’ emotional well-being. “After infections begin ebbing, a secondary pandemic of mental-health problems will follow,” The Atlantic’s Ed Yong recently wrote. “At a moment of profound dread and uncertainty, people are being cut off from soothing human contact.”

The coronavirus has laid bare the failings of American health care and public health. Without immediate action, it will do the same to America’s fragile mental-health system. Investment in that system will pay off, not just in terms of lives saved and bettered, but in monetary savings as well. The demands for money to ease economic, medical, and social problems will accelerate when the coronavirus pandemic ebbs. The United States cannot allow the needs of mental health to be pushed aside by other priorities. If that happens, the price we will pay as a society will be fearsome.