Research

December 7, 2018

2019 ACA Marketplace Premiums

Executive Summary

This study analyzes the 2019 premium increases for health insurance plans offered through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) individual marketplaces. Specifically, it compares the 2019 premiums to the 2018 premiums by analyzing the cost changes in three different plan types by rating area: benchmark Silver, lowest-cost Bronze, and lowest-cost Gold plans. It finds the following:

- Benchmark plans from 2018 that are still offered in 2019, even if not as the benchmark, rose by an average of 5 percent—the lowest average increase since the ACA marketplaces began operating;

- Only 15 percent of all rating areas have the same benchmark plan as 2017;

- The average 2019 benchmark plan premium is 1 percent higher than the average 2018 benchmark plan; and

- The lowest-cost Bronze premium increased by an average of 1 percent, and the lowest-cost Gold premium increased on average by about 14 percent.

Introduction

Now in their sixth year, the ACA’s individual market health insurance exchanges appear to be experiencing some semblance of stability. Insurers experienced much difficulty in setting premiums because of several issues: Predictions of the characteristics and size of the enrollment pool were consistently off, the regulatory burden on insurers was shifting, and promised reimbursement to insurers, in the form of cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments, eventually disappeared. Coming into 2019, however, premium levels indicate greater stability within the individual market.

This study evaluates 2019 premiums by comparing them with 2018 premiums. It finds that the cost of 2018 benchmark plans that are still sold in the individual market have increased in 2019 by an average of 5 percent for a 27-year-old non-smoker. Overall, the average 2019 benchmark plan premium is 1 percent higher than the 2018 benchmark plan premium. The average lowest-cost Bronze plan premium is 1 percent higher.

2019 Benchmark Premiums

For the first time in the exchanges’ short existence, the national average premium increase in the individual marketplace did not surpass inflation.[1] As mentioned above, it is likely that the lack of premium changes for 2019 is a result of more stability in the marketplace. In previous years, insurers struggled to predict risk pools as enrollment predictions were off and young, healthy individuals failed to enroll at the expected leaves. Furthermore, a changing regulatory burden and uncertainty regarding federal insurance policy culminated in the loss of CSR payments in 2018. Many of these problems have disappeared, however, as effectuated enrollment in the individual market has hovered around 10 million for the last few years and the biggest policy change lined up for 2019—the zeroing out of the individual mandate penalty—took place before insurers set their premiums.

One way to estimate premium growth is to compare benchmark premiums from year to year. The second-lowest cost Silver plan is referred to as the benchmark plan, as federal subsidies are calculated based on this plan. In the discussion of health insurance costs, the benchmark plan is frequently the focus because of its implications for enrollment numbers—roughly 11 percent of the individual market in 2015 enrolled in this plan.[2] Benchmark premiums also have implications for federal spending. As benchmark premiums increase, so do the tax credits provided for those eligible. Therefore, as the benchmark premiums increase, so does federal spending. When 2019 benchmarks are compared with 2018 benchmarks, 2019 benchmark premiums are 1 percent higher on average—down from a 36 percent bump last year.

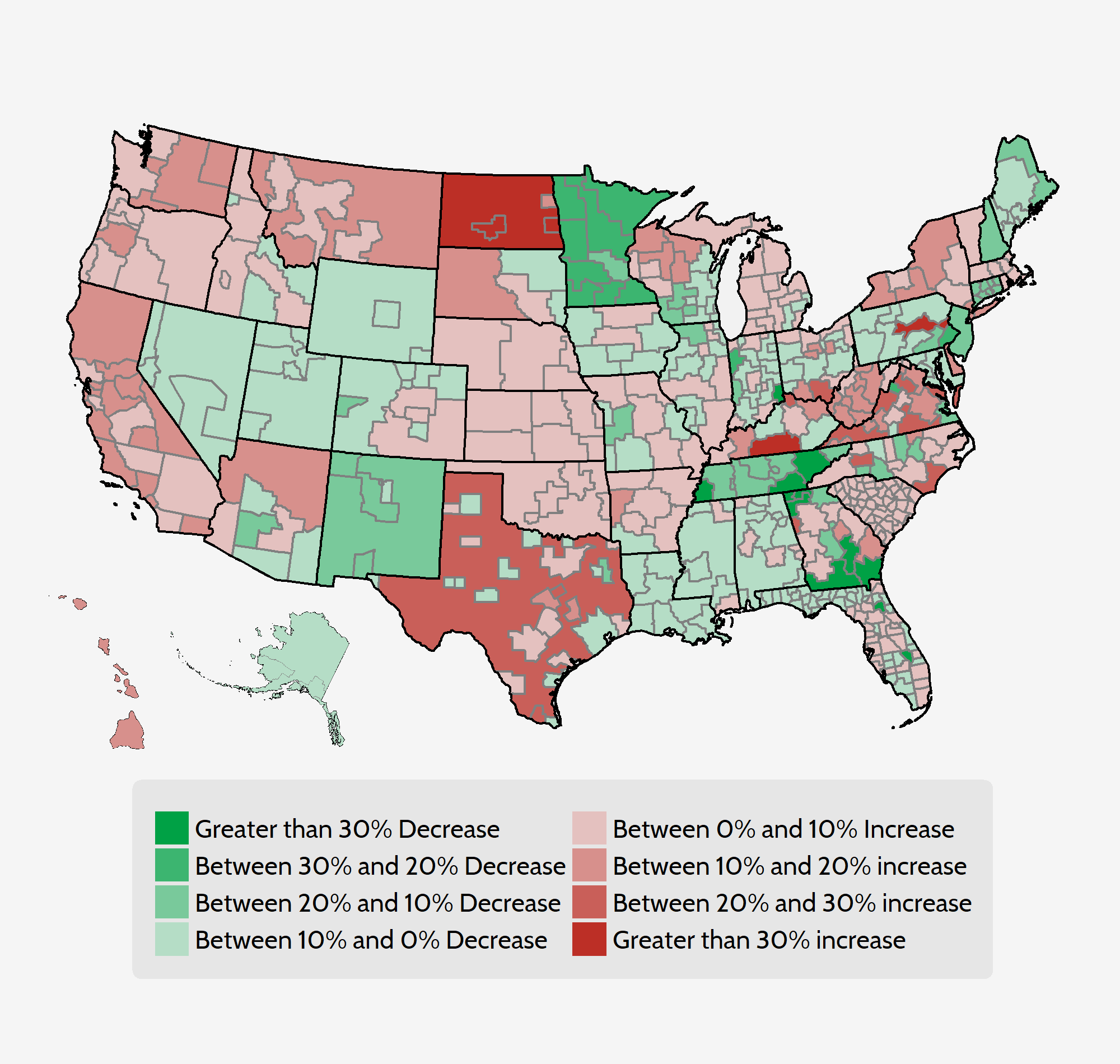

As Figure 1 demonstrates, however, one number cannot accurately summarize the differences in benchmark premiums on a national level.

Figure 1. Comparison of 2019 and 2018 Benchmark Premium by Rating Area

Despite the encouraging national outlook, averages mask a lot of this variation; therefore, it is necessary to look at the national insurance marketplace from various viewpoints to analyze premium changes accurately. The 1 percent average increase in benchmark premiums includes premium increases and premium decreases that are greater than 30 percent.

Premium changes vary across the country. Nevada, Louisiana, and Maine will all see statewide premium decreases, while in New York, Oklahoma, and California premiums are going to up. Premiums can also vary widely within states. For instance, certain areas in Kentucky will see a 35 percent increase in premiums while others will see a slight decrease. Changes in benchmark premiums for 2018 range from a 51-percent decrease in one rating area in Georgia to the 35-percent increase in a rating area in Kentucky. Both numbers represent drastic differences from the average national benchmark increase of 1 percent.

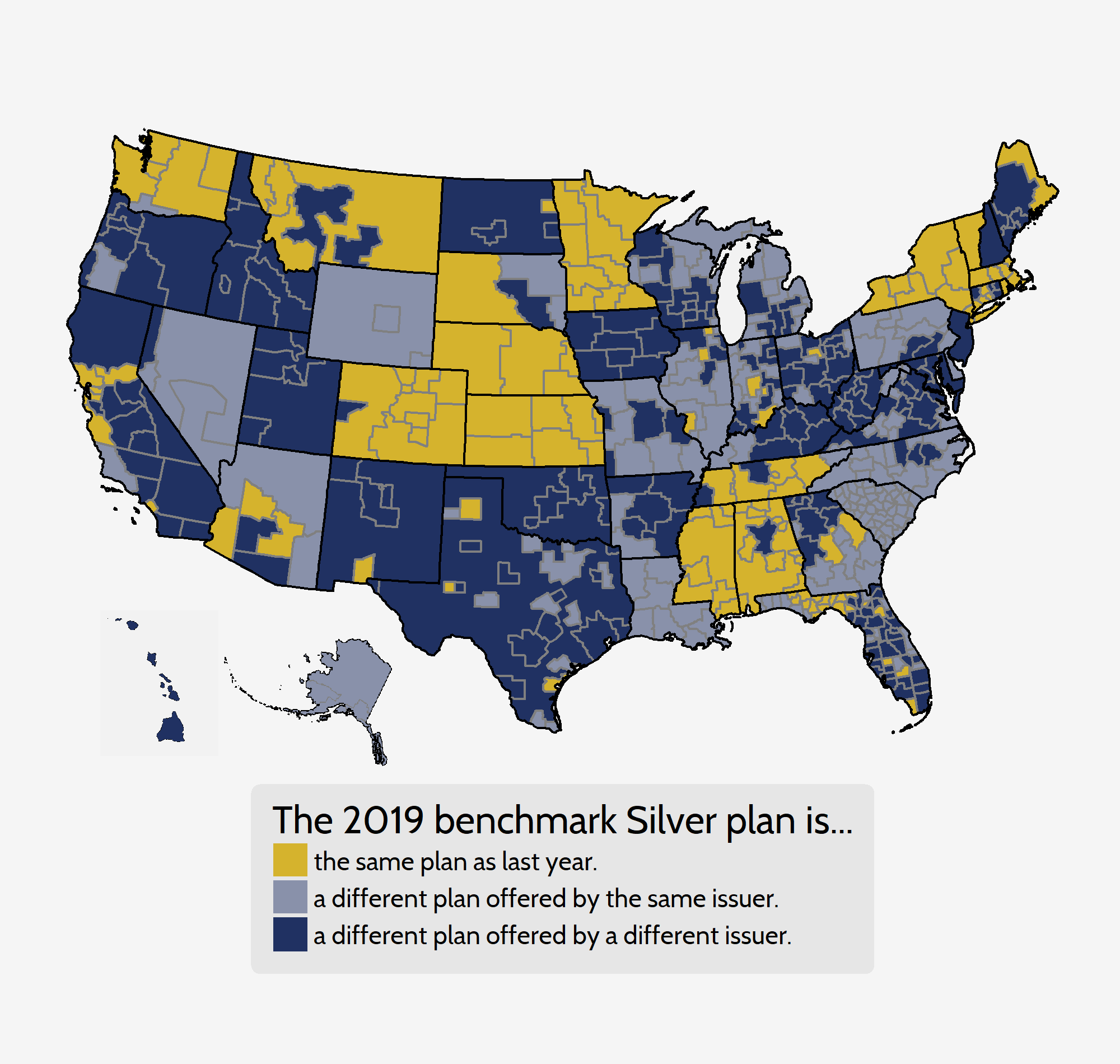

Despite the increase in stability, most rating areas still experience churn in the benchmark plan from year to year. In other words, two different plans are being compared instead of the premium growth for a single, unique bundle of benefits. As shown in Figure 2 below, in 2019 only 15 percent of rating areas feature the same benchmark plan as the 2018 plan year, though 83 percent of 2018 benchmarks are still offered on the exchanges this year. The premiums for 2018 benchmark plans that are still offered on exchanges in 2019, even if not as the benchmark for the new year, have increased by 5 percent, on average.

Figure 2. Benchmark Churn from 2017 to 2018

Looking at Gold and Bronze Premiums

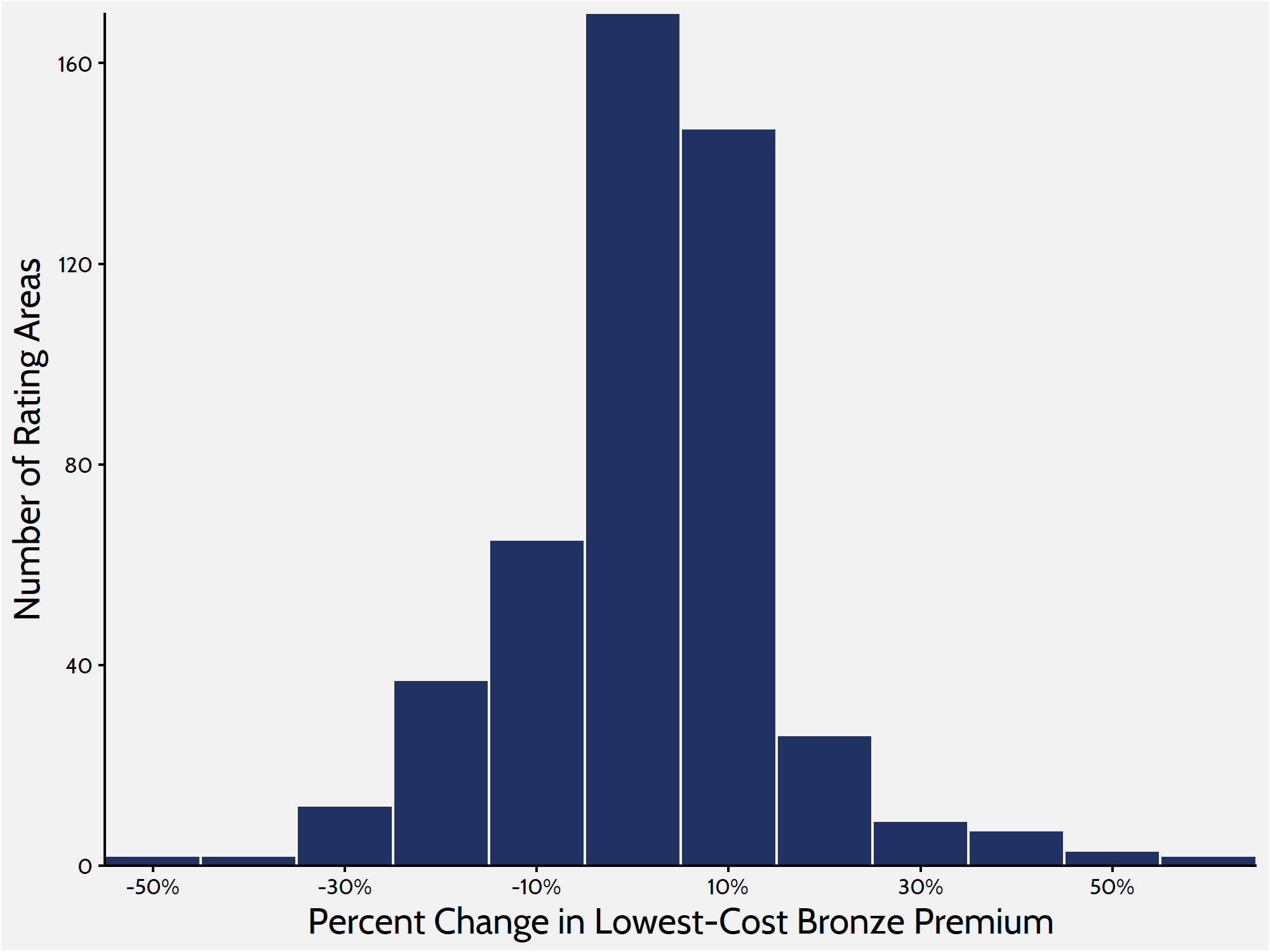

To get a more complete picture of what is happening in the individual marketplace, it is helpful to look at Bronze and Gold plans. Silver plans enrolled roughly 71 percent of the marketplace in 2017, the most recent year this data was made available, while Bronze plans—the cheapest metal level on the market—enrolled about 22 percent.[3] Looking at the lowest-cost Bronze plan in each rating area provides a more comprehensive understanding of how premium changes are affecting people throughout the market, because lower-cost plans are more likely to attract those ineligible for subsidies and cost sharing. When weighted by population, premiums for the lowest-cost Bronze plan have increased by 1 percent between 2018 and 2019.

Figure 3. Lowest-Cost Bronze Premium Increases

Gold premiums grew by a larger factor. The average lowest-cost Gold plan in each rating area is set to increase by an average of 14 percent for plan year 2019. Historically, a much smaller share of consumers enroll in Gold plans than in Silver or Bronze plans. Roughly 4 percent of individual market consumers enrolled in a Gold plan in 2017, and similar numbers purchased Gold plans in the previous years.

Table 1. Premium Increase Quartiles by Metal Level

|

Metal Level |

Minimum | 25th Percentile | 50th Percentile | 75th Percentile | Maximum |

|

Lowest Bronze |

-54% | -4% | 3% | 9% |

62% |

|

Benchmark Silver |

-51% | -5% | 1% | 7% |

35% |

| Lowest Gold | -29% | -1% | 7% | 17% |

147% |

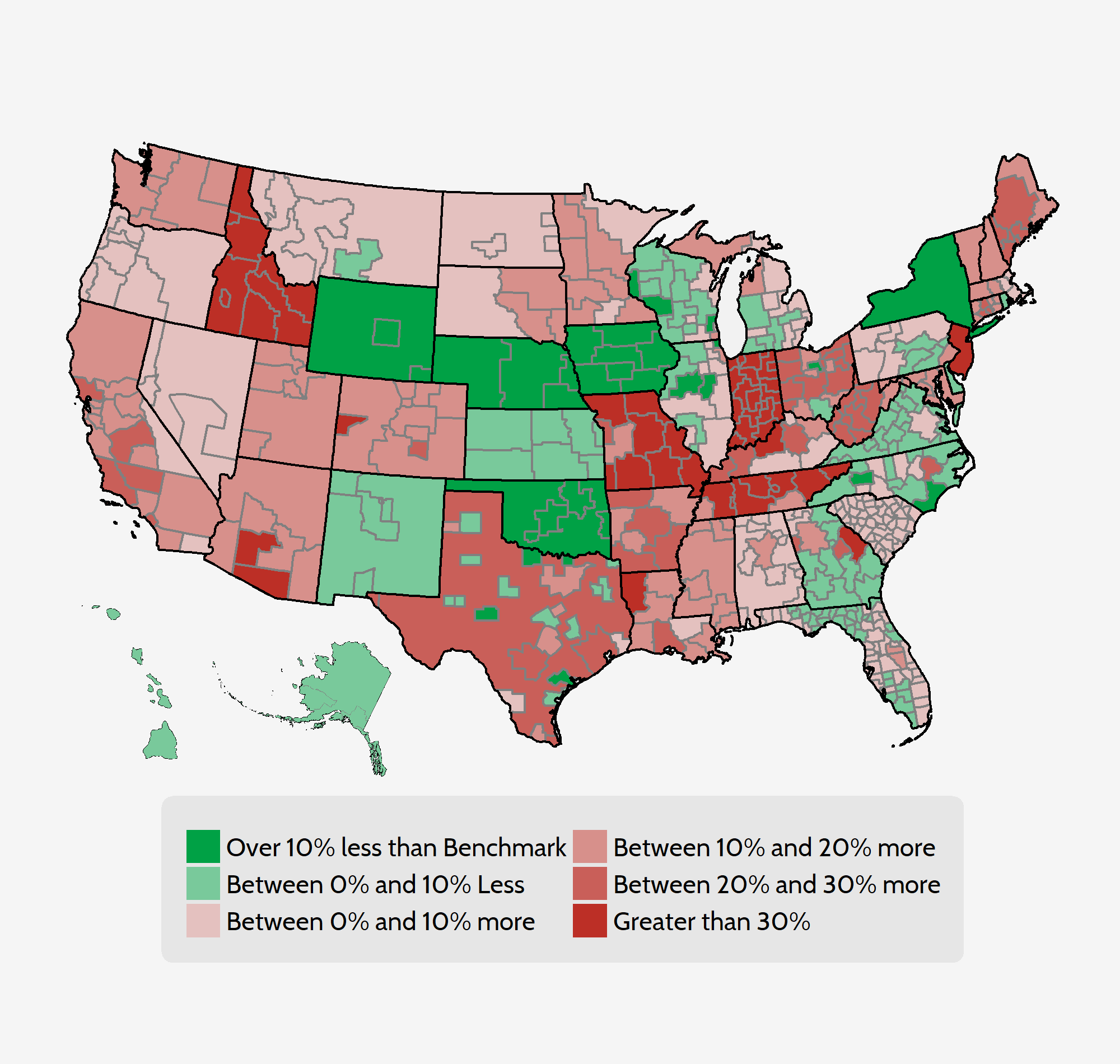

Gold plans continue to be of interest in this analysis because of the “Silver Loading” that continues to take place on the exchanges. Insurers increased premiums substantially in 2018 in response to the discontinuation of CSR payments in 2017. In order to shield consumers ineligible for subsidies, many insurers loaded the bulk of their premium increases onto Silver plan premiums. Doing so keeps prices lower for Bronze and Gold plans, giving those without subsidies better options. As a result of this “Silver Loading,” there are many areas where Gold plans are cheaper than the benchmark plan. Of the 501 rating areas, 139 rating areas feature at least one Gold plan that costs less than the benchmark Silver plan.

Under current law, households between 300 and 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level are entitled to subsidies if the benchmark premium is more than roughly 9 percent of their annual income. Because of the spike in benchmark premiums, many people in this income range may consider enrolling in Gold plans because of those plans’ smaller cost sharing—in other words, these consumers can buy higher-quality products at a cheaper price.

Figure 4. Lowest Gold Premiums Compared with Benchmarks

Insurer Competition

The most encouraging aspect of the 2019 marketplace is the increase in competition. Other federal health care programs designed around subsidized private insurance—such as Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D—show that competition among insurance companies is an important means of controlling prices. In the ACA individual market’s first year of open enrollment, research showed that a lack of competition was correlated with higher premiums and $1.7 billion in higher subsidy spending.[4] Now in the sixth year, 100 rating areas see at least one more firm enter the marketplace for 2019, and the number of rating areas with more than one firm is increasing by 39 to 357.

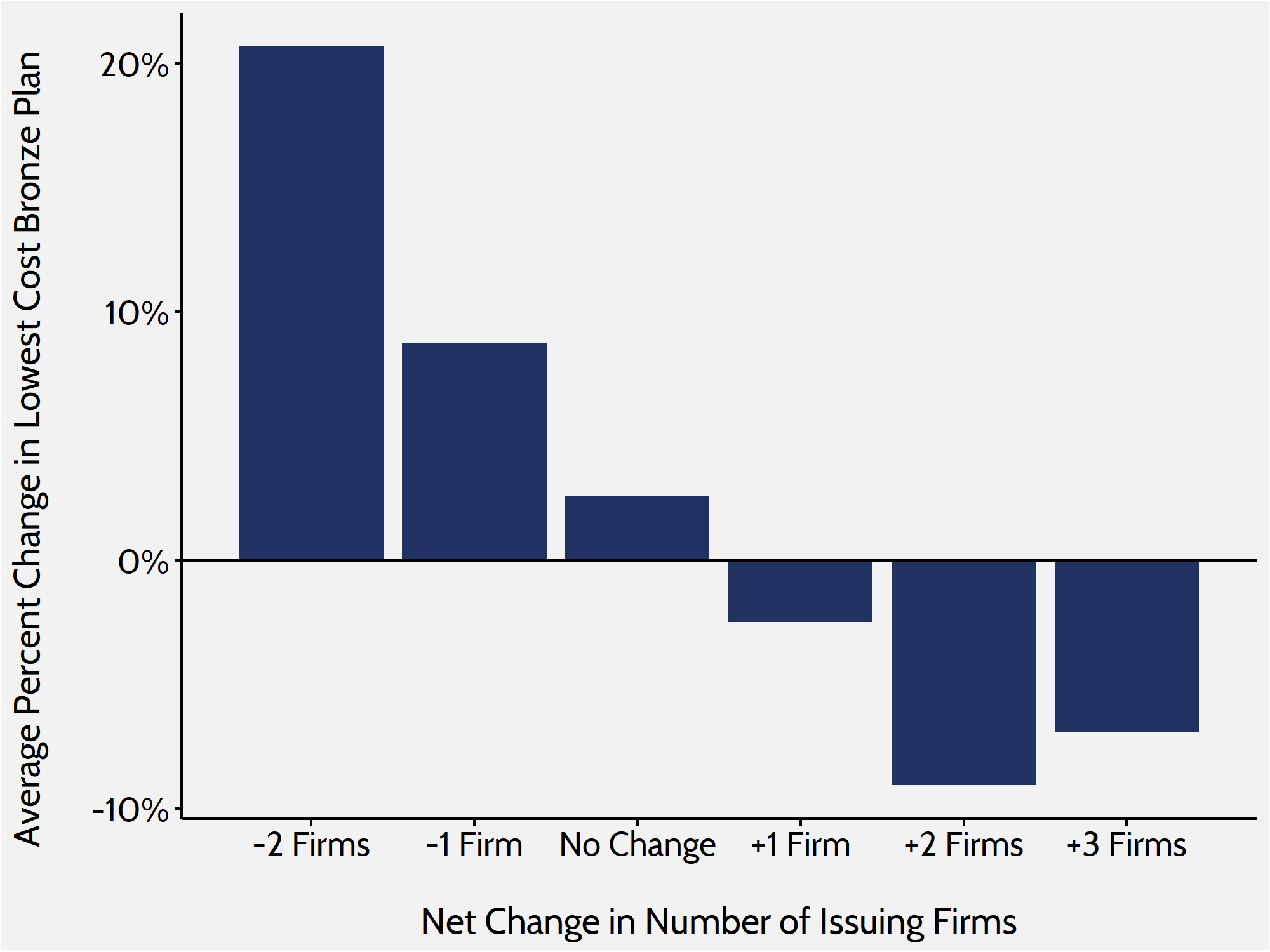

In previous research, AAF found that increased competition in the marketplace led to smaller increases in premiums. This study makes an even stronger finding: Increased competition has led to a decrease in premiums. In rating areas where competition increased, the average lowest-cost Bronze premium decreased by roughly 4 percent. In areas where competition stayed the same or decreased, that premium increased by 4 percent.

Figure 5. Bronze Premium Changes and Issuer Fluctuation

Data and Methodology

The primary sources of data for this report are the 2018 and 2019 individual market medical landscape files that are available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).[5] These landscape files contain data on the health insurance plans that were or are offered through the federally facilitated or federal-state partnership exchanges.

Health insurance costs vary between regions even within states. To adjust for these variances, the states are divided into geographic rating areas that all insurers must use as a part of their rate-setting process. This study examines premium changes at the level of rating area, to give greater granularity and precision to the analysis.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) also offers exchange data for all states from 2014 through 2019.[6] The RWJF data supplement the CMS data on federal exchanges with data on state exchanges. To fill any gaps in the RWJF data, this study uses plan-comparison tools on state-based exchanges where they are available. Overall, the study analyzes data on 2018 and 2019 Bronze, Silver, and Gold plans for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, accounting for all rating areas nationwide. The estimates on the number of health insurance issuers in each rating area are based on Silver plan data.

When computing average price changes across rating areas, this study uses the potentially eligible population in each rating area to calculate a weighted average of the change in each area. The potentially eligible population is defined as the number of individuals who are either uninsured or insured through the individual market, ineligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and determined to be a legal resident. This study estimates this population using the 2011-2013 American Community Survey.[7] All the premium estimates in this report are based on those offered to a 27-year-old non-smoker. Unless otherwise noted, the premium changes do not include any subsidies that are available to middle- to low-income households.

The ACA’s structure eliminates the need, for the purposes of this study, to calculate premium changes for different age groups. The ACA employs an age-based community rating, which limits insurers to charging older, higher-risk enrollees no more than three times as much as younger, lower-risk enrollees. Because of this restriction, age-based rates between 21 and 64 are typically a multiple of the base rate by a factor between one and three. Therefore, there is no real need to consider different ages when determining premium growth as a percentage, because each age is going to see proportional growth. For example, if a 21-year-old’s premium increases by 25 percent, then a 55-year-old’s premium will increase by 25 percent also, even though the 55-year-old is being charged more. Under current law, states may adopt a more restrictive age-based community rating than the federally mandated 3:1, which would change the ratio insurers use to calculate rates. The three states that do this for the individual marketplace are New York (1:1), Vermont (1:1), and Massachusetts (2:1).[8]

Conclusion

Though the premium changes within the marketplaces are not uniform, the 2019 marketplace features the smallest average premium increases yet. ACA exchanges still suffer from unneeded quirkiness, however. Funding CSR payments for 2020 would likely decrease premiums in the marketplace, increase enrollment, and possibly even decrease federal spending.[9] As long as insurers are required to provide high actuarial value plans at a discount rate without being compensated for these benefits, we will continue to see the “Silver Loading” we see now, and the marketplace will not be as friendly to competition as it could be.

As encouraging as the minor premium increases are, the most encouraging indicator of a stabilizing individual market is the news that more insurers are entering the exchanges. Increasing competition in the individual marketplaces will be critical to any further premium decreases as well as the long-term stability of the marketplace. The introduction of new insurers after the mass exodus of insurers beginning in 2015 is encouraging and could portend a continued slowing of premium increases in the future.

Despite the encouraging news about the 2019 individual marketplace, it is by no means perfect. There are still many problems with the ACA that need to be resolved. The individual market still suffers from an unbalanced risk pool, restrictive regulations, and stagnant enrollment—problems that have led to a cumulative 88 percent increase in benchmark premiums since 2014.

[1] https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html

[2] https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-10-26-2.html

[3] 2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 15, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Marketplace-Products/Plan_Selection_ZIP.html

[4] Gruber J, Dafny L, and Ody C, “More Insurers Lower Premiums: Evidence from Initial Pricing in the Health Insurance Marketplaces,” NBER Working Paper No. 20140, May 2014, available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w20140

[5] Individual market medical landscape files are available for download at data.healthcare.gov

[6] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, available at: https://hixcompare.org/. Data accessed on 11/5/2018

[7] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/

[8] Market Rating Reforms. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), March 15, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Market-Reforms/state-rating.html

[9] http://healthandeconomy.org/reinsurance-and-cost-sharing-reductions-estimates/