Advertisement

Redlining Was Codified Racism That Shaped American Cities And This Exhibit Shows It Still Exists

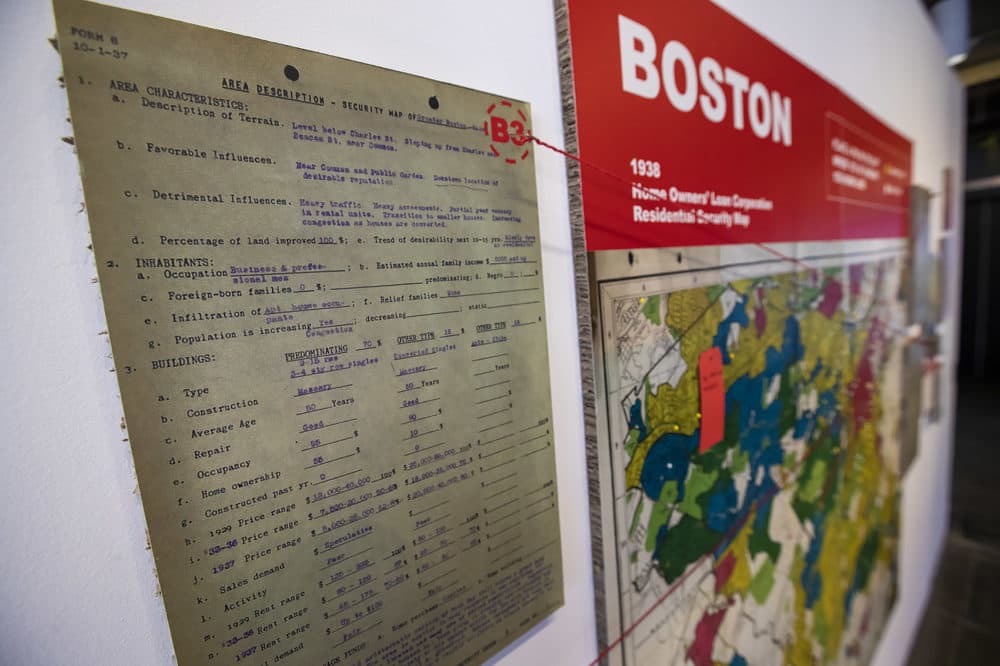

On maps from nearly a century ago created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, immigrant populations were deemed “hazardous.” The presence of black people was a “detrimental influence” or an “infiltration.” In the 1930s, these "residential security" maps served as guidelines for real estate professionals and loan officers. The maps categorized regions across the country that supposedly deserved investment and others that were considered too “risky” for mortgage lenders. The risk was based solely on the racial makeup of a community.

Stark red lines on the maps outline neighborhoods made up of people of color. Green lines mark the “safe” areas of mostly white families. The maps are codified racism.

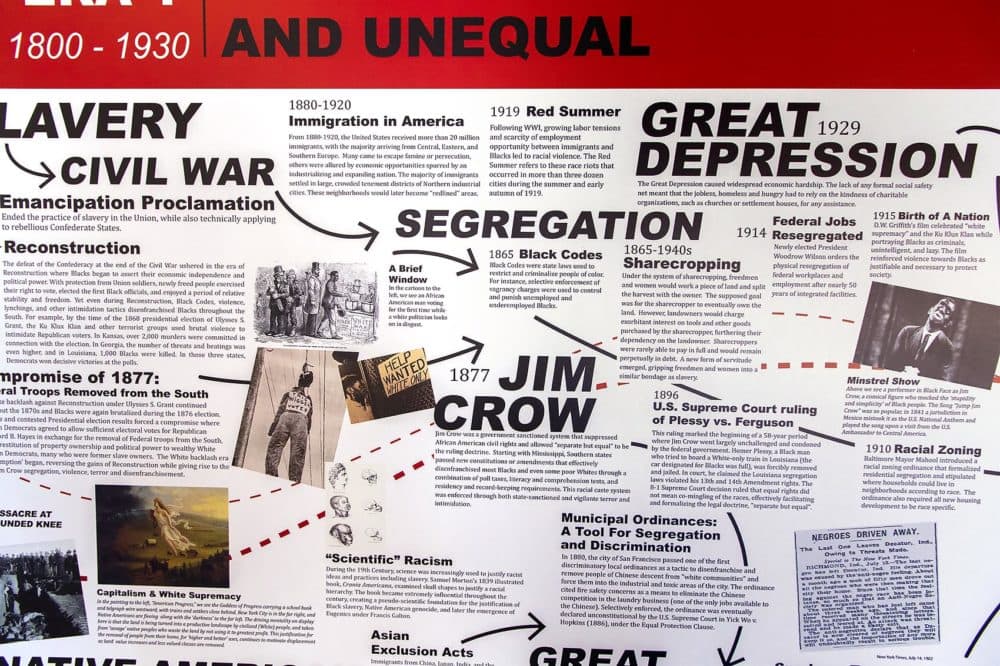

Though eventually made illegal, the blatantly racist practice scarred black Americans for generations, blocking access to capital, a proper education, government financing for homeownership and all the basic tenets for wealth-building.

Created under the New Deal, The Home Owners' Loan Corporation program was meant to ease the effects of the Great Depression. Yet, these policies destined redlined regions for disinvestment and concentrated poverty. Redlining was followed by other detrimental efforts such as urban renewal, which cleared neighborhoods to construct housing projects and highways, in turn displacing communities of color, once again changing the urban geographical landscape.

Redlining and its aftermath is the premise of a massive free exhibit currently on display at the Boston Architectural College, up through April 29. The traveling exhibit, which is called “Undesign the Redline,” looks at this discriminatory housing policy through the lens of history, segregation and discrimination.

Created by a design studio called “Designing the WE,” back in 2015, it first focused on stories out of New York and the Bronx, but has since expanded to other major American cities. April De Simone, co-founder and partner at Designing the WE, grew up in the Bronx, the daughter of a Puerto Rican mother. It’s where she watched her mother struggle to keep her home as their community changed.

“We don't know the magnitude of the collateral consequences of these policies, we're only beginning to scratch the surface," De Simone said. "Why? Because it's not a discussion that people have. So people like her are my heroes.”

The exhibit is numbered into sections, which include an introduction to redlining, a timeline, stories of those affected and how to reframe the conversation. In the last several years, it’s expanded to cities across the country such as Cleveland, Atlanta and Los Angeles. Replicas of the exhibit are up in each of those cities.

In each location, they add the local history.

“[Redlining made] skin color and class synonymous with the devaluing of property, reinforcing a perception of the ‘us’ and ‘them,’ De Simone said, “stating [that] if a certain ‘element’ comes in, at all costs, you have to try to keep them out because that's how you'll maximize your value.”

Since January, De Simone has traveled from New York to Boston on a weekly basis to co-teach a seminar at the Architectural College called, “UnDesign the Redline: The Transformation of Place, Race, and Class in America” with Katherine Swenson, the vice president of design and sustainability at Enterprise Community Partners, a national nonprofit geared toward designing affordable homes that offer opportunity such as jobs, education, health care and convenient transit. The two organizations partnered together to host the exhibits nationwide.

"We've been talking a lot about issues around perception ... what makes a good neighborhood?" Swenson said. "Part of what this exhibition does is it reveals the structural underpinnings of how decisions are made and what is happening below the surface that is creating the kind of inequities that we see."

The two instructors have challenged a classroom of aspiring architects to research, interview community members, and ponder an important question: What would it look like to begin to undo decades of of inequality? Approaches mentioned in the exhibit include learning from people's lived experiences, providing a framework for trust and equity, and creating spaces to heal traumas.

“This is not a history that I've ever learned before,” said Molly Schmidt, a second-year master's student at the architectural college. “It was really shocking and kind of emotional and but felt like a relief, like I'm not crazy, there's evidence that there are things that are wrong in our built environment and there's actually reasons why.”

One group of students focused on East Boston and the ongoing challenges of evictions. They found, unsurprisingly, that East Boston, like Dorchester and other neighborhoods, continue to be shaped by structural racism and biased ideas of what makes a "good or a bad" community.

Schmidt’s group found that the perception of East Boston as a place that's "deteriorating" and plagued by a bad element was propagated even by local government. It was used as an excuse for private development to build more "desirable" areas, bulldozing existing infrastructure for more "desirable" populations. A prime example occurred in 1969 when Massport officials seized properties along Neptune Road by eminent domain to make more room for Logan Airport. It led to the destruction of the beloved seaside destination on the Emerald Necklace called Wood Island Park.

Schmidt said when her group talked to a community organizer in East Boston, he said the neighborhood needed a memorial that gave a glimpse of these stories of displacement. It would be one way to remember those families who were driven out of their homes in the name of progress. He also told her they need raw data, but those numbers are difficult to track as new immigrants may not feel empowered or have the language ability to fight these illegal housing practices. A landlord may sell a property and issues eviction notices in English to clear out the building.

"We seek to reframe East Boston's most valuable asset as its resilient community," the students wrote in their presentation.

Alissa Marcano Santelli, a 23-year-old college student who is originally from Curaçao, said the issue of housing instability hits home. Moving to Boston was a culture shock after growing up on an island for much of her life and finding stable and affordable housing in the city has been a challenge. She currently lives in a basement apartment.

“In the three years I've been here, I'm going to be moving the fourth time,” Marcano Santelli said.

There’s trauma that can accompany such abrupt fluctuations, the lack of power in seeing a neighborhood change or being priced out of your home, De Simone says. She hopes this exhibit sheds light and that her students will use what they learned to design more equitable and welcoming communities.

"For me this exhibition is an indictment on that you could do these things with impunity," De Simone said. "It's saying no more. We're going to talk about this and it's going to have each of us reflect and look in the mirror and ask ourselves how are we complicit in this system?"

To Ben Goodman, a third-year student at the architectural college getting his master's in landscape architecture, change begins with conversations like this and by including community stakeholders in the process.

"There's seems to be not enough opportunities or even interest in having discussions about how much of an effect spatial designers can have on the communities that experience them ... how to actually best serve that community and not just the clients," Goodman said. "So I'm really grateful that we've had the opportunity to participate in this discussion."